The Blind Spot of Application-Centric Thinking: Business Capabilities Matter

by Daniel Lambert

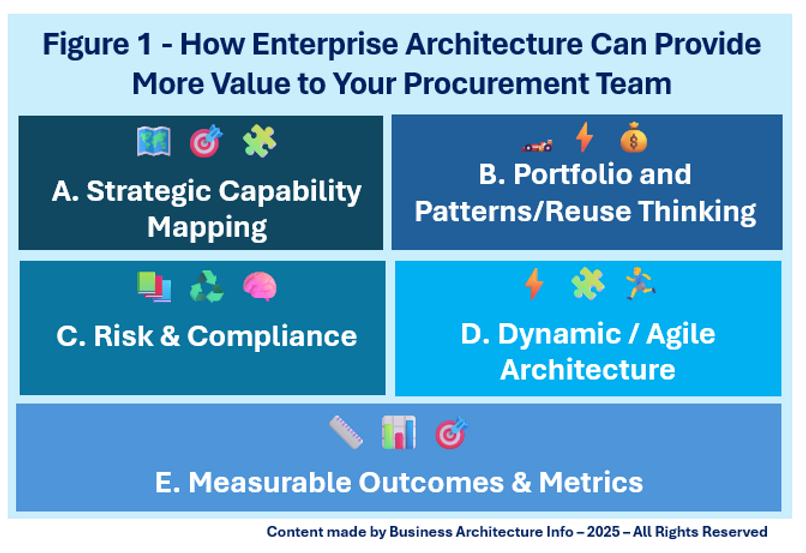

Organizations continue to equate digital transformation with technology implementation. As a result, enterprise architects often focus on application architecture, optimizing systems rather than enabling strategy. Driven by speed, vendor influence, and limited business maturity, this app-centric approach has become the default. Yet, without connecting technology to business capabilities, as shown above, transformations remain superficial, misaligned, and costly. True enterprise agility begins not with applications, but with clearly defined business capabilities.

Why EAs Focus Mostly on Application Architecture

Many enterprise architects find themselves immersed in application architecture because organizations have historically defaulted to technology-first transformation. Despite decades of failed or underperforming initiatives, companies still gravitate toward application-first thinking. There are four main reasons that explain this behavior, as shown in Figure 1 below.

-

Technology-Centric Mindset. Organizations often assume that software implementation alone can deliver transformation. IT and vendors have long been the gatekeepers of change, promoting new systems as silver bullets. The result? Business stakeholders equate transformation with technology adoption, not business redesign.

-

Perceived Speed and Cost Efficiency. Implementing a new system feels faster and cheaper than engaging in a rigorous process or capability redesign. A new application can be procured and deployed within a quarter; rebuilding processes or capability models takes months and cross-functional commitment. Leadership under time pressure often opts for the seemingly “quick win.”

-

Vendor Influence and Pre-Built “Best Practices”. ERP, CRM, and SaaS vendors aggressively promote standardized “best practices” and pre-built templates. Many organizations take the bait, shaping their processes to fit the software instead of defining what the business actually needs. This creates a dependency on technology-defined structures rather than business-defined design.

-

Lack of Capability Maturity. Finally, most organizations simply lack the internal maturity to sustain a capability-first approach. Without documented capabilities, processes, skilled analysts, or strong governance, the complexity of redesigning business architecture feels daunting. Thus, the application-first route becomes the path of least resistance. The outcome is that enterprise architects are pulled into an application-centric vortex, building roadmaps, rationalizing portfolios, and optimizing integrations, while the true value-creation lens of business capabilities remains underused or misunderstood.

The Importance of Application Architecture

To be clear, application architecture does matter. It provides the technical foundation on which digital business runs. When done well, it enables scalability, interoperability, and agility, as demonstrated here:

-

Operational Efficiency and Integration. A coherent application architecture eliminates redundant systems, simplifies integration, and supports consistent data flows. This improves operational efficiency and reduces technical debt — essential for cost control and IT resilience.

-

Governance and Standardization. Application architecture also enforces governance. It defines boundaries, ownership, and standards for development and deployment. This helps prevent the uncontrolled sprawl of shadow IT and enables compliance with internal and external regulations.

-

Agility and Scalability. In an age of cloud, APIs, and microservices, well-architected applications allow enterprises to pivot faster — whether scaling operations, entering new markets, or enabling new digital channels.

-

User and Customer Experience. Applications remain the tangible interface between business and customer. A well-designed application landscape supports consistent, intuitive, and data-driven experiences across touchpoints.

In short, application architecture is a vital pillar of enterprise architecture. However, its benefits are limited if not anchored to what truly drives business value: business architecture and business capabilities.

The Limits of Application Architecture

The problem arises when application architecture becomes the only lens through which transformation is viewed. Applications describe how things are done, not what the organization must be able to do. When EA focuses solely on applications, it risks three major drawbacks:

-

Technology-Led Transformation. Transformation becomes defined by system boundaries rather than strategic intent. The business is forced to adapt to software logic rather than the other way around. As Decker notes, this often leads to the abandonment of process-first or capability-driven initiatives.

-

Fragmented Business Alignment. Application portfolios often map to organizational silos rather than enterprise value streams. Without a capability-based alignment, redundancy and misalignment persist, even after expensive modernization efforts.

-

Limited Strategic Insight. Applications can tell you where costs lie, but not why they exist. They reveal dependencies but not business priorities. In short, they describe the “plumbing,” not the “purpose.” As a result, decision-making stays reactive, focusing on maintenance and upgrades instead of strategic investment.

This limitation is why leading architects increasingly emphasize the need for capability-based thinking, a business-first lens that defines what the enterprise must achieve before deciding how to enable it.

The Cost of Not Using or Having Inadequate Capabilities

As highlighted in Why Your Business Capabilities Are Superficial—and What It Is Costing You, many organizations operate with incomplete or shallow capability models. The consequences are tangible and costly, as mentioned in Figure 2 and below:

-

Misaligned Investments. Without a well-defined capability map, organizations cannot effectively prioritize technology spending. Investment decisions get driven by short-term projects, political influence, or vendor persuasion, not by strategic capability gaps.

-

Operational Inefficiency. When capabilities aren’t clearly defined or measured, duplication and inefficiency thrive. Different departments end up solving the same problem in parallel, using different systems, methods, and data definitions.

-

Strategic Blind Spots. Superficial capabilities prevent leadership from understanding the organization’s true strengths and weaknesses. When external shocks, either by new competitors, regulations, or technologies, occur, the organization reacts slowly because it doesn’t know which capabilities to enhance or protect.

-

Transformation Fatigue. Perhaps the biggest cost is human and cultural. When transformation is driven by tools instead of purpose, teams lose trust in change initiatives. Employees see projects come and go, with minimal real improvement in how the business operates or delivers value.

In short, discarding business capabilities leads to waste, confusion, and erosion of competitive advantage, all under the guise of “digital transformation.”

Business Capabilities Matter

Business capabilities define what an organization must be able to do to execute its strategy. They are the stable, strategy-anchored elements of enterprise architecture, the connective tissue between vision, process, and technology.

As outlined in How to Build a Grounded Capability Model, grounded capabilities are built on evidence, not assumptions. They represent the true operational DNA of the enterprise, linking strategy to execution, as shown below:

-

Capabilities Anchor Strategy. They provide a language that both business and IT understand, bridging the traditional communication gap between them. Strategic goals can be translated into capability changes, which in turn guide investments, process redesign, and application evolution.

-

Capabilities Enable Agility. Because capabilities are stable and business-oriented, they become the reference model for change. Instead of restructuring applications or processes each time strategy shifts, organizations can assess which capabilities to strengthen, outsource, or automate.

-

Capabilities Enhance Governance and Transparency. A mature capability model creates traceability — from strategic objectives down to system components. It allows leadership to see exactly how strategy execution depends on particular parts of the enterprise. That visibility is invaluable for decision-making and portfolio management.

In short, capabilities are not an academic exercise; they are the backbone of business transformation and the foundation of enterprise coherence.

The Benefits of Linking Applications to Business Capabilities

The ultimate goal is not to dismiss application architecture, but to connect it to the business capability model. When applications are explicitly mapped to capabilities, the enterprise gains a clear line of sight from technology spend to business value.

-

Investment Clarity. Architects can identify where systems overlap or under-support key capabilities. This alignment allows for precise rationalization — reducing redundant tools while ensuring critical capabilities are well-enabled.

-

Transformation Roadmaps That Matter. By linking capabilities and applications, transformation initiatives become business-driven, not tool-driven. Programs can be sequenced based on capability maturity and strategic importance, rather than arbitrary system replacement cycles.

-

Portfolio Governance and Transparency. This linkage provides an evidence-based way to govern IT spend. Executives can visualize which business areas depend most on legacy systems, and where modernization will yield the highest business impact.

-

Accelerated Agility and Innovation. When applications are mapped to modular capabilities, the organization can adopt new technologies selectively — evolving faster without destabilizing the enterprise foundation.

In essence, capability-linked application architecture transforms enterprise architecture from a documentation exercise into a strategic management discipline. It helps leaders see technology not as the driver of change, but as the enabler of well-defined business capabilities.

Application architecture remains vital, but it must support, not define, the enterprise. Without grounded capabilities, organizations risk investing in technology without achieving transformation. Linking applications to business capabilities creates transparency, strategic alignment, and measurable value. It shifts enterprise architecture from a technical exercise to a business discipline. In the end, sustainable success depends less on the software we deploy and more on the capabilities we choose to strengthen.